Anacyclosis, Act 3: The Rise and Fall of Democracy

What causes the rise of democracy? What precipitates its fall? And what can anacyclosis tell us about the future of America and other major powers? Building on the work of the previous two posts, we can finally try to answer these questions.

But first, a brief recap. In “Anacyclosis, Act 1,” we explored the difference between monarchy and tyranny, and explained why the former tends to degenerate into the latter. In “Act 2: Rise of Republics,” we discussed the key forces that, when acting together, can propel an autocratic state away from one-man-rule and towards constitutional rule. In the anacyclosis model, this paradigm shift is represented by the transition from tyranny to aristocracy. In this post, we will consider the final three stages of the cycle, viz. oligarchy, democracy, and ochlocracy (often translated as “mob rule”).

A Note on Terminology

As mentioned in the previous post, in recent discussions on the global history of democracy, the term “democracy” has sometimes been used to encompass virtually any non-monarchical regime displaying any kind of cooperative governmental structure. Under this view, ancient Athens, the Huron of North America, and the Republic of Venice were all democracies.

This new taxonomy effectively lumps all regime types into only two categories—autocracy and democracy—thereby glossing over important distinctions between the various species of both autocratic and constitutional rule. By contrast, the classical typology of regime types, which the anacyclosis model makes use of, helpfully distinguishes between two forms of autocratic regime (monarchy and tyranny) and no less than four species of non-autocratic government (aristocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and ochlocracy).

We see no reason to abandon this rich taxonomy in favor of the new simplistic one. Granted, it is sometimes useful to focus on the distinction between autocratic and non-autocratic regimes, as we did in the previous post. However, there is no reason to make the word democracy, which has always had a more specific meaning, into a blanket label for all non-autocratic regimes, especially since there already are at least two terms that have been used throughout history for that purpose, viz. republic and constitutional state.

Another reason not to call all non-autocratic regimes democracies is that when a state first makes the leap from autocracy to republic, it rarely ever exhibits the features of a full democracy right away. Athens and Rome (in ancient times) and the Netherlands and Britain (in modern times) did not approach what we might call democracy until centuries after they first abolished or severely restricted the power of their monarchs.

Granted, there are some cases where an autocracy suddenly becomes a democracy, but this usually happens through the help or intervention of a foreign (usually democratic) power, as happened with South Korea and Japan after WWII. In most newly-born republics, however, power is initially shared only among an elite group. In the language of anacyclosis, such a regime is called an aristocracy.

How Democracies Emerge

Now the big question: Once a state gets rid of its monarchy (or curtails its power) and establishes an aristocratic republic, how does it go on to eventually become a full-blown democracy? Our research suggests that the very same forces which drive the shift from one-man-rule to a republic will eventually cause a further diffusion of power resulting in a democracy if they continue to obtain over an extended period of time.

In the last post, we posited three key factors that, when working together, drive the paradigm shift from autocracy to republic. Most republics, we said, emerge within clusters of wealthy states that experience 1) rapid and prolonged economic growth, 2) intense inter-competition between the states of the cluster, and 3) some form of colonization that acts as a pressure-release valve to ease the tensions caused by overpopulation and elite overproduction. Finally, we argued that republics are rare in history because these three factors rarely coincide over extended periods of time. Only three major waves of republics are known in the historical record: the first happened in the ancient Mediterranean, the second in late medieval Italy, and the third is the one we are in currently.

If our present hypothesis (that the three factors above will eventually produce democracy if they continue long enough) is true, then we would expect to observe three things about democracies in history: 1) they should be rarer than aristocracies, since not all aristocracies will continue to experience the above confluence of factors, 2) they should only emerge in clusters of wealthy states that have already produced aristocracies, and 3) the ebb and flow in the number of democracies should track the ebb and flow of aristocracies but with a time lag.

Indeed, the historical record seems to confirm all three points. Democracy in the strict sense has only ever emerged in two waves—one in the ancient Mediterranean ecosystem of republics and the other during the modern wave of republics currently unfolding (the much smaller wave of medieval Italian republics was evidently too short-lived to produce democracy). In both cases, democracies became common only after the spread of aristocracies (i.e. elite-run republics).

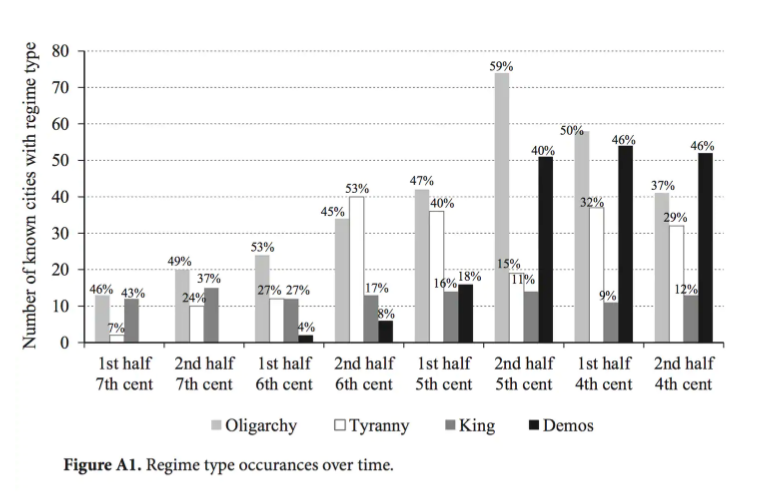

Take a look at this fascinating chart from David Teegarden’s book on ancient Greek history called Death to Tyrants!

This chart classifies all ancient Greek city-states into four regime types and tells us what percentage of states had what kind of government during each half-century between 700 and 300 BC. Note that this classification scheme is not exactly the same as the one found in the anacyclosis model. Here, oligarchy basically means “rule by the few” and thus includes both aristocracy and its degenerate form (which is called oligarchy in the anacyclosis model). Similarly, demos here refers to any popular regime and thus includes both democracy and its degenerate form, ochlocracy.

Despite these terminological differences, the above chart clearly shows that the wave of democracies in the ancient Mediterranean was, as we would expect, slightly smaller than the wave of aristocracies (here called “oligarchies”) and that the democratic wave did not get started until over a century after aristocracies had emerged and were growing in number.

For those who are interested in the details, the reason why this chart begins in 700 BC is that we do not have good historical records from earlier than that. It cuts off in 300 BC because no one has yet undertaken the huge amount of work needed to classify and catalog the Greek city states of the period from 300 BC to the Roman conquest. Aristocracy and ochlocracy are not represented because the team that undertook the project of compiling this data was not interested in the theory of anacyclosis. Finally, the reason why the percentages within most blocks in the chart add up to more than 100 is that whenever a city-state experiences a regime change, it is counted twice (once as each regime type it exhibits).

One final thing to note about this chart is that the data it is based on is very incomplete. There were over 1000 ancient Greek city-states during the period represented. We only have reliable data for a small fraction of them. One day in the future, when we can secure enough funding at the Institute, we would like to lead an effort to expand the database this chart is based on to extend to 50 BC, to incorporate non-Greek (e.g. Phoenician, Italic, and Etruscan) city-states, and to include all six regime types.

Besides nicely illustrating how democracies follow in the wake of republics, this chart also provides a quite compelling illustration of the sequence of the stages of anacyclosis we have covered so far. Monarchy, which was the norm in the second millennium BC, is already rare by 700 BC, when this chart begins, and it continues to decline over the next few centuries. Stage 2 of anacyclosis (tyranny) peaks in the late 6th century. Then, aristocracy-oligarchy peaks in the late 5th century. Finally, democracy-ochlocracy peaks in the 4th century.

Let us now turn to the stages of anacyclosis we have yet to discuss in detail: oligarchy, democracy, and ochlocracy. As mentioned in part 1 of this series, the relationship between an oligarchy and an aristocracy or between an ochlocracy and a democracy is analogous to that between a tyranny and a monarchy. Just as a tyranny is a degenerated monarchy, so too an oligarchy is a late-stage aristocracy that has become factious and unstable through the effects of elite overproduction and LII (the “law of increasing inequality”). Likewise, an ochlocracy is a late-stage democracy that has become polarized and volatile because of those same historical trends.

In order to see these distinctions in a more tangible way, let us consider the political evolution of a country we all know quite well: the United States of America.

America’s Journey through Anacyclosis

The Framers deliberately designed the US constitution as a mixed form of government so that it would resist the effects of anacyclosis. As one can see in this essay by John Adams, they were inspired by Polybius, who had eloquently argued that the reason the Roman republican constitution had proved so robust and long-lasting was that it combined elements of all three “good” archetypes (viz. monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy). The new US government was designed so that its democratic procedures would be balanced by aristocratic elements (e.g. the Senate and Supreme Court) and a monarchic element (the presidency). However, neither Polybius nor the Framers thought that any state could be 100% anacyclosis-proof. Thus, just as Rome was dragged slowly but surely through anacyclosis, so too America has, at different times, resembled different archetypes in the cycle.

When considering how “democratic” a republic is, it is important to keep in mind that there is no universal metric by which democracy is measured. One state may possess one democratic feature—say secret ballot—but not allow for plebiscites, and vice-versa. One republic may select jurors by lot, but have no term limits, or establish a limited but yet wide franchise, or have a unicameral or bicameral legislature. There are countless permutations of democratic procedures, policies, and institutions which may contribute to the strength of the democratic element of a state. There has never been a democracy in history whose government did not also include non-democratic features. Not each and every possible democratic feature must be present within a republic before it can be accounted democratic.

Moreover, in the life of a state, these features may accrete like layers in a republic’s constitutional history, with new and expanding democratic innovations accumulating over time. Which is also to say that when judging how democratic a republic is, some consideration must also be given to the ambient political environment—to the practices of neighboring and rival states similarly situated—as well as to preceding and subsequent political changes.

When the US was founded, it was certainly democratic by Eighteenth Century standards, and was more democratic than many ancient republics. From a legal and constitutional standpoint, the US Constitution gave a substantial share of power to the democratic element. Indeed, the US would have appeared extremely democratic to French and Italian contemporaries. However, it was not initially a pure democracy, strictly speaking, because the people did not have a direct say on affairs of state and less than a fifth of the population could vote.

For these reasons, the archetype of government in the anacyclosis model that early America most closely resembled was actually an aristocracy. This claim may sound strange to modern ears, because today the word “aristocracy” refers to a rich, decadent, hereditary elite. That is not the sense in which the early US was an aristocracy. Early America was actually remarkably egalitarian compared to virtually any other country in the world at the time. And that is precisely why aristocracy, and not oligarchy, is the fitting label.

According to Aristotle, Polybius, and other ancient thinkers, an aristocracy is a constitutional state which is ruled by the few and where—this is key—the few are not merely the rich. There is some other standard(s) by which rulers are selected. America resembled an aristocracy early on because it was a constitutional republic ruled by men who had distinguished themselves in learning and/or in service to their country.

By the late 1800’s, America was showing symptoms of the next stage of anacyclosis: oligarchy. What is the difference between an oligarchy and an aristocracy? The most visible difference, as explained by Aristotle, is that in an oligarchy, the people who hold real power are not chosen based on merit, but are simply the ultra rich. (Politics 1279b5-1280a5) Despite early America’s tremendous economic growth and the opportunities that westward expansion afforded to the lower classes, the unavoidable trends of LII and elite overproduction still took their course, eventually yielding the Gilded Age, in which less than one percent of the population held over half of the country’s wealth.

As one wealthy New Yorker wrote in 1889, “It matters not one iota what political party is in power or what President holds the reins of office. We are not politicians or public thinkers; we are the rich; we own America; we got it, God knows how, but we intend to keep it if we can by throwing all the tremendous weight of our support, our influence, our money, our political connections, our purchased Senators, our hungry Congressmen, our public-speaking demagogues into the scale against any legislature, any political platform, any presidential campaign that threatens the integrity of our estate.”

As a result of LII and elite overproduction, the period between 1860 and 1920 was not only highly unequal but also quite violent, according to data analyzed by historian Peter Turchin. Besides the Civil War, there were many riots, labor strikes, massacres (such as the Ludlow massacre), and political violence (e.g. the assassinations of presidents Lincoln and McKinley).

During the second half of the 19th century, America continually experienced two of the three factors that, we said, lead to democracy, viz. economic growth and colonization (of the West). The one key factor it did not experience was intense competition with the other rich and powerful states. That all changed with WWI and WWII.

The two world wars, and especially the second one, shifted the balance of America’s mixed constitution towards democracy, the fourth archetype in ancyclosis. That is not to say that America was undemocratic before then. What we mean is that the democratic element within America’s mixed government became more prominent during the post-WW2 era. That is when inequality dropped dramatically, the middle class boomed (thanks largely to such initiatives as the GI Bill), and political equality and voting rights were expanded more than ever before.

Once again, however, LII and elite overproduction gradually took their course. Today, the middle class has been hollowed out, inequality is rapidly reaching Gilded Age levels, and our elites are more divided than they have been since the Civil War. Thus, one could say that our government is degenerating into democracy’s vicious twin: ochlocracy. What are the visible features of an ochlocracy? According to Polybius they are the subversion of free speech, the formation of political mobs, and the emergence of demagogues who pander to their mobs. (Histories 6.9.5)

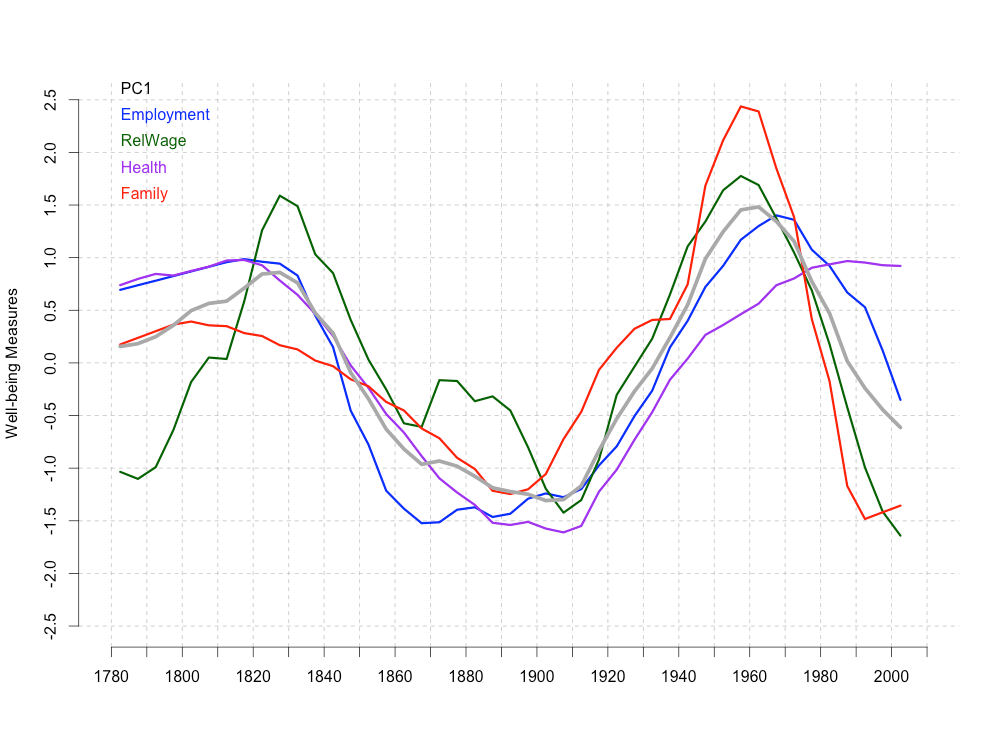

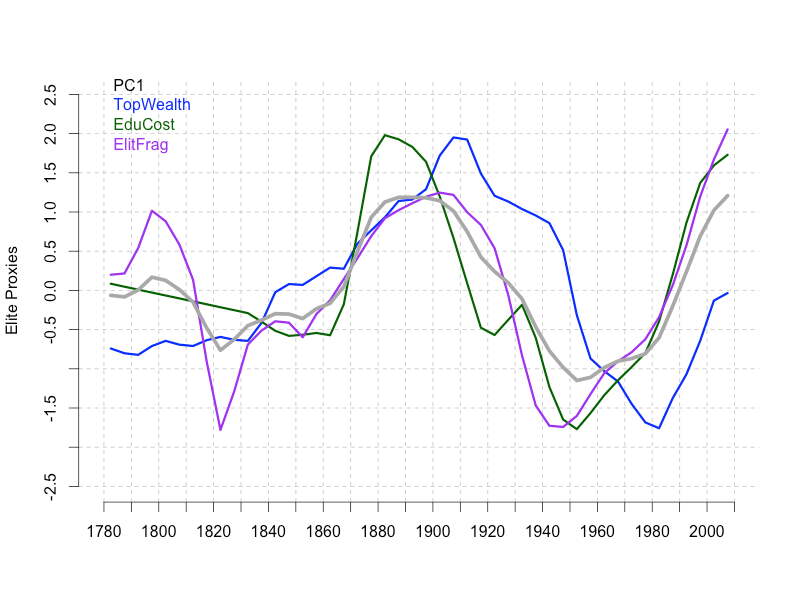

Let’s take a look at a couple of charts from Peter Turchin’s work that help illustrate these four phases that America has gone through. Turchin is not an advocate of anacyclosis, but these charts are nevertheless illuminating for our purposes.

In this first one, we see various proxies for the general well-being of the American population plotted throughout American history. As we can see, well-being was high during early America—the period we labeled as aristocracy. It then fell dramatically during the late 1800’s when America exhibited the features of aristocracy’s degenerate form: oligarchy. It rose again during the mid 20th century, as America became more democratic. Recently, well-being has been falling once again, as people are noticing that we are beginning to see symptoms of ochlocracy.

The above chart highlights another aspect of America’s anacyclotic journey. Here we see several proxies for elite overproduction. As we can see, the two times in our history when we have had way too many elite aspirants clamoring for wealth and status (something that often leads to factionalism and civil strife) have been the period we labeled as oligarchy and our current age of early-stage ochlocracy. For more information on these charts and the data they show, click here.

The Future of America

If America has indeed been developing just as the anacyclosis model predicts, then what lies ahead? That is difficult to say, since America’s future may very well depend on geo-political developments beyond its borders more than on domestic politics. What will happen during the coming showdown between China and America that some experts are anticipating? How will emerging economic powers like Brazil and India, as well as established military powers like Russia, affect that geo-political face-off?

Anacyclosis is not a crystal ball that can predict exactly what will happen in the future. What it can do is help you narrow down your predictions to a few possible outcomes. In the case of America’s near future, the anacyclosis model points to two scenarios that are most likely.

One potential outcome is that America becomes a full-blown ochlocracy, just as happened to the Roman Republic in its final century. Inequality will continue to rise. The middle class, once financially independent, will become a dependent class. Our streets will be filled with homeless and demoralized people, who will depend on hand-outs and subsidies.

While these impoverished people will no longer have any financial independence, they will still remember the days when they or their parents were financially independent and had political agency. In other words, they will be habituated to demand a voice in politics, even though they will no longer be able to meaningfully challenge the political forces they depend on. Thus, a permanent mob will be born, the likes of which has never yet existed in America. Unscrupulous leaders will seek to win the allegiance of the mob, giving rise to a tournament of demagogues that will erode what is left of our institutions and pave the way towards tyranny and our own Caesar.

The other potential outcome is that America reinforces its democracy. This, however, can only happen if an independent middle class is built up again. When the middle class goes away, so does democracy, as observed already by Aristotle. (Politics 1295a-1297a)

The last time democracy bloomed in America, it took the devastation of two world wars to get our elites to invest in the people, thus creating a strong middle class. Is there a way for us to build a new middle class without another similar existential crisis?

Perhaps if we realize that rapidly rising inequality at the expense of the middle class is an existential threat to our democracy—more dangerous than any external foe—we will muster the resolve to enact policies that will preserve the middle class and our republic. One such policy proposal can be found at: rationism.org.

—––––––––

Notice: the Anacyclosis Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational organization and does not officially advocate any policy idea, political party, public official, or candidate for public office. Any policy concepts which arise from our research are referred out to separate organizations for further development and all advocacy activities. The Anacyclosis Institute is not responsible for and has no control over any content presented on or by any third-party websites or organizations.

Fair use for all images reproduced above is claimed under 17 U.S.C. § 107.

2 Comments

Please check out my new book, American Ochlocracy: Black Lives Matter & Mob Rule, 2021.

Check out my newest book “American Ochlocracy: Black Live Matter & Mob Rule,” 2021

Ron Libby/Users/ronaldlibby/Downloads/thumbnail-6.png

Recent Comments