Anacyclosis, Act 2: The Rise of Republics

Abstract: In the previous post, we discussed the difference between the first two stages of anacyclosis, viz. monarchy and tyranny. Tyranny was shown to be a late-stage form of monarchy, in which certain economic and demographic trends destabilize the state and create the conditions and incentives for revolution. In this article, we will explore how some societies are able to make the leap from one-man-rule to a constitutional system in which power is distributed across an elite group. In the language of anacyclosis, we will explore the transition from tyranny to aristocracy.

One of the most interesting episodes in Herodotus’ Histories (written c. 420 BC) involves the ascension of Darius the Great to the throne of the Persian Empire. Darius came to power in 522 BC, following a coup d’état in which he and six other Persian noblemen assassinated the previous monarch, who they claimed was a tyrant and an imposter.

Following the assassination, these seven ring-leaders held a debate about what kind of government to replace the old regime with.1 One of the seven gave an eloquent speech in favor of democracy.2 Another advocated for an aristocratic republic.3 Finally, Darius himself asserted that monarchy was the way of their ancestors and, hence, the best course for the future. The remaining four co-conspirators who had not yet spoken backed Darius. A few days later, Darius became the new king.

This report from Herodotus is interesting for three reasons relevant to our discussion. First, it represents perhaps the earliest surviving articulation of the three-part classification of political regimes (into rule by one, rule by a few, and rule by the many) that lies at the heart of most subsequent Greek and Roman political thought. Later thinkers, such as Aristotle and Polybius, would further refine this classification scheme by subdividing each of the three categories into two subtypes—a “good” and a “bad” (or “degenerate”) version. For example, one-man-rule is subdivided into monarchy (good) and tyranny (bad). Similarly, rule by a few has a good form (aristocracy) and a degenerate form (oligarchy).4

Another interesting aspect of Herodotus’ account is that it illustrates a point we made in the previous post about the possible outcomes of tyrannicide. While a revolt of the nobility against an autocrat may lead to the next stage of anacyclosis (i.e. an aristocratic republic), more often than not it acts like a reset button, whereby the state reverts to some form of one-man-rule. In this case, at least two of the Persian nobles wanted to abolish the monarchy and establish some kind of constitutional system. In the end, however, monarchy was reestablished.

The third noteworthy point about this “constitutional debate,” as it is referred to in the scholarship, is that most scholars today believe it never happened. They think that Herodotus either made it up or heard it from someone who did.5 This view seems driven in part by the long-held assumption that only the Greeks and Romans were interested in non-monarchical systems. By contrast, the Persians were supposedly committed monarchists who never even considered implementing any of the types of constitutional regime found among their neighbors to the west.

However, in recent decades, more and more evidence has come to light that societies across the world and in many time periods have made the jump from monarchy to some kind of cooperative system where power is diffused among a ruling class. For example, this 2017 article from Science lays out the evidence for “democratic” societies existing in Mesoamerica before the Spanish takeover. While we do not have any texts from the time period, archeological evidence and stories that were passed down to the Spanish colonizers suggest that several centers of power were ruled by a kind of senate, as opposed to an absolute monarch. More recently, in a book hot off the press called The Decline and Rise of Democracy, NYU historian David Stasavage makes the case that democracies have arisen in many disparate regions of the world throughout history.

In light of this new research, Herodotus’ claim that the Persians held a constitutional debate does not seem implausible. But the point of this article is not to vindicate Herodotus’ account. Rather, it is to explore a few interesting questions that Herodotus’ account raises—questions that are being debated today with renewed vigor, now that the major democracies of the world are in crisis. What causes certain societies to reject autocracy in favor of a constitutional system? And why did most societies in history, including the Persian empire, not make that shift, even though the idea was available to them?

To be clear, Stasavage’s basic point that democracy was common to many premodern societies around the world is not new. Cambridge historian Paul Cartledge compiles and addresses such claims at the beginning of his 2016 book Democracy: A Life. While Cartledge acknowledges that non-monarchical, cooperative governments may be found throughout history, he pushes back against the claim that they can be accurately characterized as democracies. He argues that in the premodern world, only ancient Athens (and other Greek democratic poleis) developed the kind of laws and institutions that enabled direct participation on such a massive scale that the people (demos) could be said to hold real power (kratos).6

Thus, it may be a stretch to use the term “democracy” in the way that Stasavage and others have used it. In fact, both Stasavage and the Science article mentioned above concede that what they call democracy was a far cry from what we understand that term to mean today.7 They seem to use “democracy” to refer generally to any non-monarchical regime in which power was shared among a ruling class and where there were cooperative structures in place that allowed for commoners to have some say in public affairs.

In order to avoid a terminological inexactitude, let us refer to such regimes going forward as republics or alternatively as constitutional regimes. While these phrases have several meanings, they both have a long history of being used as umbrella terms encompassing any and all non-monarchical systems.8 So, to rephrase the million dollar question that Stasavage and countless other historians since antiquity have tried to answer, What causes the paradigm shift from autocracy to constitutional regime?

Most historians across the centuries have answered this question in the abstract, appealing to metaphysical notions of freedom, progress, or certain “values” that somehow came to be embraced by Europeans alone. More recently, some historians have tried to answer such “big questions” in terms of concrete and quantifiable factors, such as economic, demographic, and geographic ones.9 However, this particular question has yet to be answered through such methods in a rigorous and convincing manner.

It is, of course, beyond the scope of a simple blog post to settle the debate about how republics are born. Nevertheless, we would like to suggest a method for approaching this question, and to highlight three key factors that we believe have been crucial in driving the paradigm shift from monarchy to constitutional regime throughout history.

While this paradigm shift may have happened in many places since time immemorial, there are only three instances in history where it happened on a large scale and for which extensive written evidence survives. Those three instances are 1) the ancient Mediterranean, which saw over a thousand city-states (not only Greek but also Phoenician, Etruscan, and Italic) move away from monarchical rule, 2) northern Italy in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, where a handful of republics emerged, and 3) the modern wave of republics that started with the American and French Revolutions and has now spread to much of the globe.

In attempting to explain the transition from monarchy to republic, looking to where the evidence is most abundant and well-documented seems like an obvious place to start. And yet, as far as we know, there is no major study comparing these three waves of republics in an effort to figure out what common factors may be at work. We find this surprising. If there is such a comparative work that we are unaware of, please let us know in the comments below.

Based on our research, the first postulate we would like to propose is that constitutional regimes come and go in groups or “waves.” In other words, with few possible exceptions, one does not find isolated democracies or republics popping up here and there across history. Rather, when they appear, they appear in clusters of interconnected societies that all transition away from monarchy within a relatively short historical period. Another way to think of this is that republics come and go in ecosystems. This is not only true of the three major waves mentioned above, but seems to hold more generally. For example, in the case of Mesoamerican “democracies” discussed in the Science article, there is not just one but rather a plurality of different sites spread across the region that archaeologists believe may have been republics.

If we accept this postulate that republics come and go in clusters, what can we say about the factors that drive the emergence of an ecosystem of republics? One way to try to answer this question is to look for characteristics that are shared by the three major waves of republics just mentioned but absent from most other societies in history. The next step would be to narrow down these unique characteristics to the few that seem most responsible for the paradigm shift.

Through this method, we have arrived at three key factors that, we suggest, played a major role in driving the rise of republics:

First, we can observe that in each of these three major waves, the cluster of states that made the leap away from monarchy contained probably the richest states in the world at the time in terms of per capita wealth. For example, Athens, Syracuse, Miletus and other Greek poleis were astronomically wealthy (per capita) compared to other states of the time period, such as Egypt or the Persian Empire.10 The same holds for Venice, Florence, and Genoa in the late Middle Ages, as it does for the United States and the European republics of the modern era. From now on, we will refer to this as the “economic growth factor.”

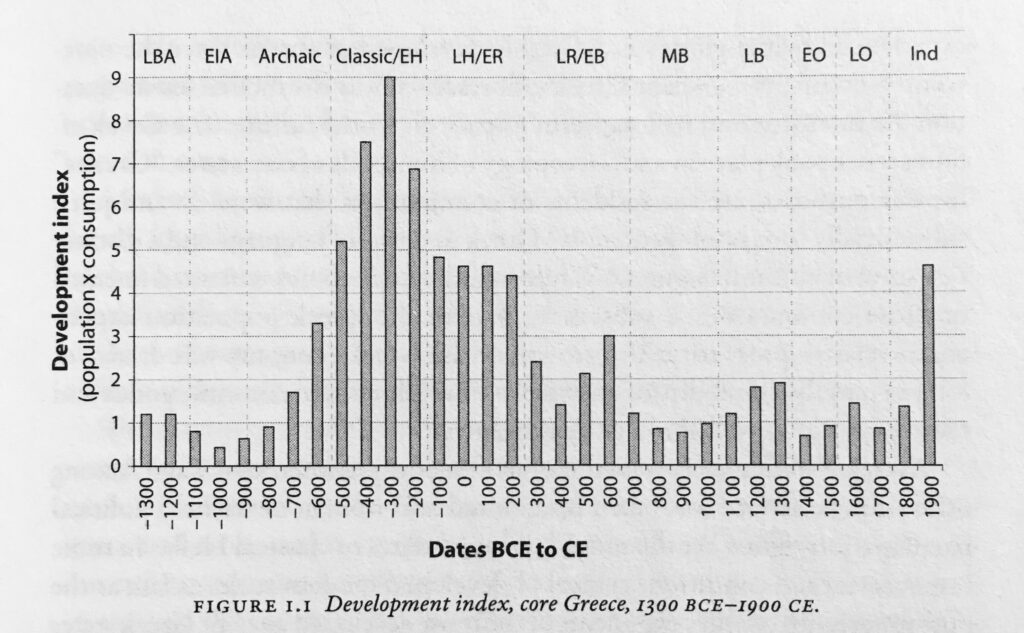

This chart, from Josiah Ober’s The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece, shows how ancient Greece reached a level of prosperity that would not be seen again in that part of the world until the 20th century! The “development index” here is defined as the population estimate (in millions) × the median per capita consumption estimate (in multiples of bare subsistence). Amazingly, this economic flourishing tracks very closely the rise and decline in the number of democratic poleis in the region (though this is not indicated in the chart).

The second factor that seems to have driven the shift was intense military and economic competition within these three ecosystems of unusually wealthy states. The ancient Greek city-states were notoriously always at war with one another, as were the medieval Italian republics, and as were the modern European powers. We will call this the “competition factor.”

Finally, the third key factor that all of these three ecosystems had in common was some form of colonization. This should not be confused with colonialism. While medieval Venice and many modern European powers engaged in predatory and extortionary practices associated with the latter term, the ancient Greeks and Phoenicians engaged in colonization—i.e. the founding of new colonies—in ways that did not involve the subjugation of local peoples. They did this by settling areas of sea-coast that were of little value to local tribes, who often welcomed the founding of a new trading hub that offered access to international goods.

What colonization offered to the states of all three waves of republics was not just economic expansion but, more importantly, a sort of pressure-release valve for overpopulation and elite overproduction (a concept discussed in the previous post). In the ancient Mediterranean ecosystem of republics, it was quite common for states suffering from civil strife to ease tensions by sending off part of their population (often volunteers) to form a new colony. A similar pressure-release valve was available to modern Europe, from which millions of people emigrated to the Americas or Australia. Let us, then, call this the “pressure-release factor.”

It bears mentioning that these three factors have been severally discussed at length by many historians in a number of contexts. For example, Stasavage includes inter-state military competition in his short list of factors that he claims lead to democracy.11 More notably, Josiah Ober includes all three of them in The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece among a long list of factors that he claims drove the economic efflorescence and political evolution of ancient Greece. What we are suggesting is that these three factors in particular also played an important role in the two waves of republics that have occurred since antiquity, and thus seem to be of particular importance.

If this is correct, then how might these three factors help explain the rise of republics? While a full explanation of their synergistic effects would require a book-length treatment, we can offer here a brief summary of our current thinking on the matter.

The move from autocracy to republic (just as the move from republic to full democracy) involves decentralizing power and expanding the deliberative apparatus of the state to include people further down the hierarchy. Historically, there is one type of event that has proven most effective at driving such top-down concessions: an existential threat to a nation posed by an adversarial power. This is where the competition factor comes in.

When faced with an existential foreign threat, a king will often give concessions to the elites and/or the elites will give concessions to the commoners in an attempt to raise troops, boost morale, or reward troops who have made great sacrifices for the state. One can see this even in recent American history in the case of the GI Bill, which rewarded Americans who fought in WWII and helped create the largest middle class in history.

However, fierce competition between states (which causes such existential moments to arise), does not seem to be enough to push autocratic regimes over the edge to adopt and maintain a constitutional system. Both China and India went through many periods where they were divided into fiercely inter-competitive kingdoms. But this competition was not enough to effect a paradigm shift.

This is where the economic growth factor comes in. Judging from the historical record, it seems that rapid economic growth sustained over a long period of time is another essential condition that, when combined with the competition factor, can succeed in driving the decentralization of power and the formation of cooperative structures. Such rapid and protracted growth did not occur in premodern India and China for geographic reasons. Even during “warring states” periods, the various kingdoms in those regions were mainly dependent on domestic production and trade with their neighbors for economic growth. By contrast, the republics of the ancient Mediterranean, medieval Italy, and modern Europe drove much of their economic growth through maritime trade far beyond their own borders, thanks largely to accidents of geography.

This is not to say that India and China never flourished economically; they certainly did. However, their periods of flourishing were never as long as in the case of the republics we have been speaking of. For example, Britain has now experienced virtually uninterrupted economic growth since the 11th century, and it only became a democracy after over 800 years of that trend. Similarly, Athens and Rome each experienced over 500 years of economic development before they reached their most democratic form. By way of comparison, no Chinese dynasty in the past two millennia lasted more than three centuries, and the earlier Han only lasted four. Only in the three clusters of republics mentioned do we see the competition and economic growth factors working in tandem over many centuries.

Finally, in order for a republic (or any regime) to last, it has to address the problem of elite overproduction, otherwise further coups or revolts will again topple the government. Interestingly, a similar point is already present in the constitutional debate reported by Herodotus. One of the arguments Darius lodges against aristocratic republics is that they are unstable, rife with strife, and tend to quickly revert back to some form of monarchy.

This seems to be why the third factor—colonization—was crucial historically. Besides contributing to economic growth, colonization acted as a pressure-release valve for overpopulation and elite overproduction. Whenever there were too many elite aspirants in one of these republics, some of them could go overseas and seek their fortune elsewhere, thus easing tensions back at home caused by elite over-competition.

In the case of the United States, the western frontier provided such a pressure-release valve for much of American history. This is in no way a justification of American westward expansion, but simply a statement about the socioeconomic and demographic effects it had on the early US. After the frontier was closed, America found new ways of expanding outward through its position as world superpower—at least up until recently. Interestingly, some historians have argued that the political turmoil that has been growing in America over recent years has happened because American expansion has ground to a halt for the first time.

In sum, protracted economic expansion, intense international competition, and some sort of pressure release valve for elite overproduction are three key factors we believe played a decisive role in catalyzing each of the three well-documented waves of republics in history. While this hypothesis may not be as attractive as explanations that appeal purely to moral progress and the struggle for freedom, it is based on observable and measurable historic trends.

Moving forward, if we want to defend the ideal of democracy, we need to be honest about how our current wave of republics got started. And if we want to encourage its spread without the negative manifestations of the three factors above (e.g. frequent warfare and invasive economic expansion) we need to understand why they were conducive to the development of republics in the past.

Notes

1. Herodotus Histories 3.80-83.

2. Interestingly, the term Herodotus uses is not demokratia but isonomia, meaning “equality before the law.” At the time of his writing, demokratia had not yet been established as the standard term for popular rule.

3. The term he uses is actually oligarchia. However, this usage does not carry the negative connotations that the word would acquire with later writers such as Aristotle and Polybius. For Herodotus, oligarchia simply means the rule of the few.

4. The passage where Polybius discusses these subdivisions may be read on our archive by clicking here. Aristotle offers an almost identical classification of government types (Politics 1297b 5-10), with one interesting difference. While Polybius calls the good and bad forms of popular rule democracy and ochlocracy (i.e. mob rule), Aristotle calls the good form politeia (often translated as republic in English) and the bad form democracy(!)

5. One prominent theory is that Herodotus derived the material for the three speeches of the constitutional debate from the political philosophy of Protagoras (whose writings do not survive). This was suggested by F. Lassère in 1976 and more recently by Paul Cartledge in his Demoracy: A Life (p. 96). Interestingly, Herodotus seems to have faced skepticism already in his own day about whether the constitutional debate really happened. He prefaces the debate by saying, “Some Greeks refuse to believe that [these speeches] were actually made at all. Nevertheless, they were.” (Histories 3.80) This emphatic defense of his account is highly unusual for Herodotus, who freely admits uncertainty about many of the stories he reports.

6. See Cartledge Democracy: A Life, pp. 2-4.

7. See Stasavage The Decline and Rise of Democracy, p. 8.

8. A regime need not have an enshrined document titled “The Constitution” (as does the USA) in order to be a constitutional regime. The term constitution is often used to signify a body of laws (whether written or oral) that bind an entire community. Under this definition, both the modern UK and ancient Sparta qualify as constitutional states.

9. Such as Walter Scheidel, Ian Morris, Josiah Ober, and Peter Turchin, to name a few.

10. See Ober The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece, pp. 79 ff.

11. See Stasavage The Decline and Rise of Democracy, p. 7, second paragraph.

Recent Comments